This week, some of Virginia’s rural health districts have begun the second round of COVID-19 vaccines, in addition to immunizing people in group 1B. That's putting a strain on health districts on the Eastern Shore, Middle Peninsula and Northern Neck.

Down the road from the county fairgrounds, among farm fields, a line of vehicles stretch for over a half-mile beyond the entrance to a makeshift vaccine clinic at the Volunteer Rescue Squad building in the town of Warsaw. Among the police and health care workers sitting in their idling pickup trucks and SUVs are watermen, farmers, truck drivers, who also serve as volunteer first responders. Volunteers with clipboards direct them.

Parked in a field next to the squad building are people who have had their shot. They must wait inside their parked vehicles for 15 minutes until they are checked out. Volunteers like nursing student Aaron Goetz are helping a stretched staff.

“’Did you receive a second shot card?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Yes, we did.’ ‘Ok, alright, you guys are good. Thank you.’”

Sara Headley, a nursing professor at Rappahannock Community College, heads the team of nursing students.

“So, our nursing students are playing an integral part in helping our local health department get all these vaccines out to our providers and our community,” Headly says.

For vaccination teams, the day lasts 12 to 14 hours as they vaccinate some 400 to 500 people. The available vaccines are finicky. It’s stored in freezers that send out an alarm if the temperature fluctuates. And the vials must be handled with extra care.

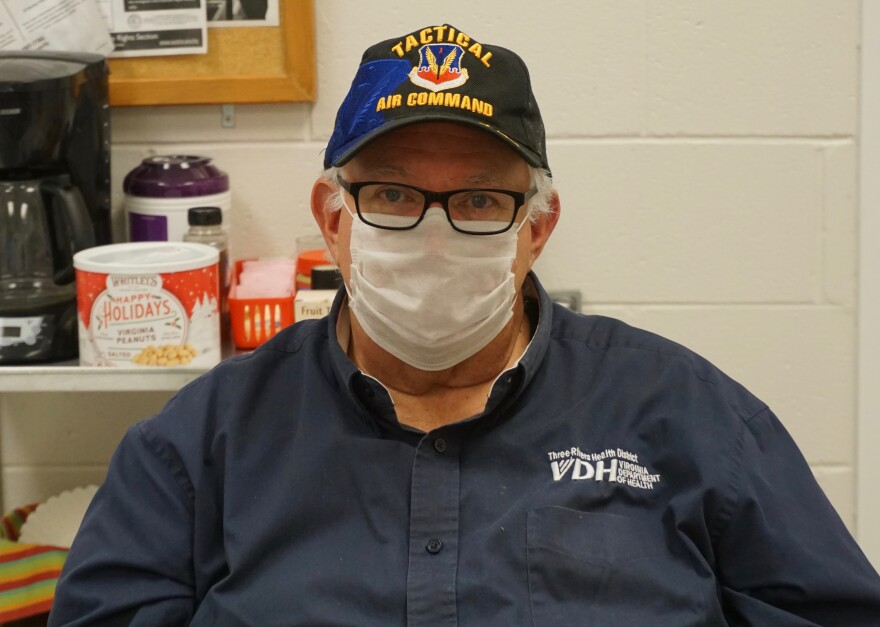

“Messenger RNA is very delicate stuff. So, if you take a vial of this vaccine and shake it, it’s toast, it’s done,” says Dr. Richard Williams. He directs 12 rural counties in Three Rivers Health District and across the Chesapeake Bay at the Eastern Shore Health District. Both run on small budgets and staff.

“I’ve had physicians who’ve been in practice in this area for 30 years say, 'Look the health department ain’t anything like it was 30 years ago,’” he explains.

Dr. Williams served 27 years in the Air Force and another 20 at NASA. He’s always on the phone or in a meeting, trying to build an army of vaccinators despite the current national vaccine shortage.

“This is an extraordinarily challenging situation. We have to constantly try to increase our capability of vaccinating people and accommodate new doses at the same time we’re vaccinating again the people we already did,” says Williams.

Facing down the shortage, last week, Dr. Danny Avula who heads the state vaccine effort said any lag in data entry will affect whether a district gets vaccines. Rural communities are known for poor broadband access. And the vaccine management system or VAMS is heavily dependent on that technology.

“We have started this using the old reliable phone call, paper type trail but that means our data enterers have to enter every encounter individually into VAMS,” he says.

To make do with what they have the state is rationing.

“We may have the capability to do 500 but because we’ve rationed vaccine elsewhere to try to be geographically equitable and reach vulnerable populations we may only have enough to do a 200 person,” Williams explains.

Dr. Williams says this campaign will take five to six months.

“I was involved in two armed conflicts personally in the Air Force, I’ve been involved personally in five or six different hurricanes, every pandemic we’ve had – H1N1, Zika, SARS-1, MERS, anthrax in Washington, D.C.," he says. "This is the hardest thing I’ve ever done, it is the hardest thing I’ve ever done.”

On the heels of the vaccine effort – this week northern Virginia had the first case in the state of a COVID-19 variant that is known to spread faster.

This report, provided by Virginia Public Radio, was made possible with support from the Virginia Education Association.