Researchers at William & Mary’s Center for Conservation Biology have spent years trying to understand what’s happening with ospreys in the Chesapeake Bay.

Anecdotally, residents including homeowners and sportfishers, report seeing fewer birds, and the center has conducted surveys showing drastic declines in osprey pairs living in certain areas, such as the seaside of the Eastern Shore.

The group’s latest study sought to assess the population baywide.

“This was a major effort,” said Bryan Watts, professor and director of the conservation biology center.

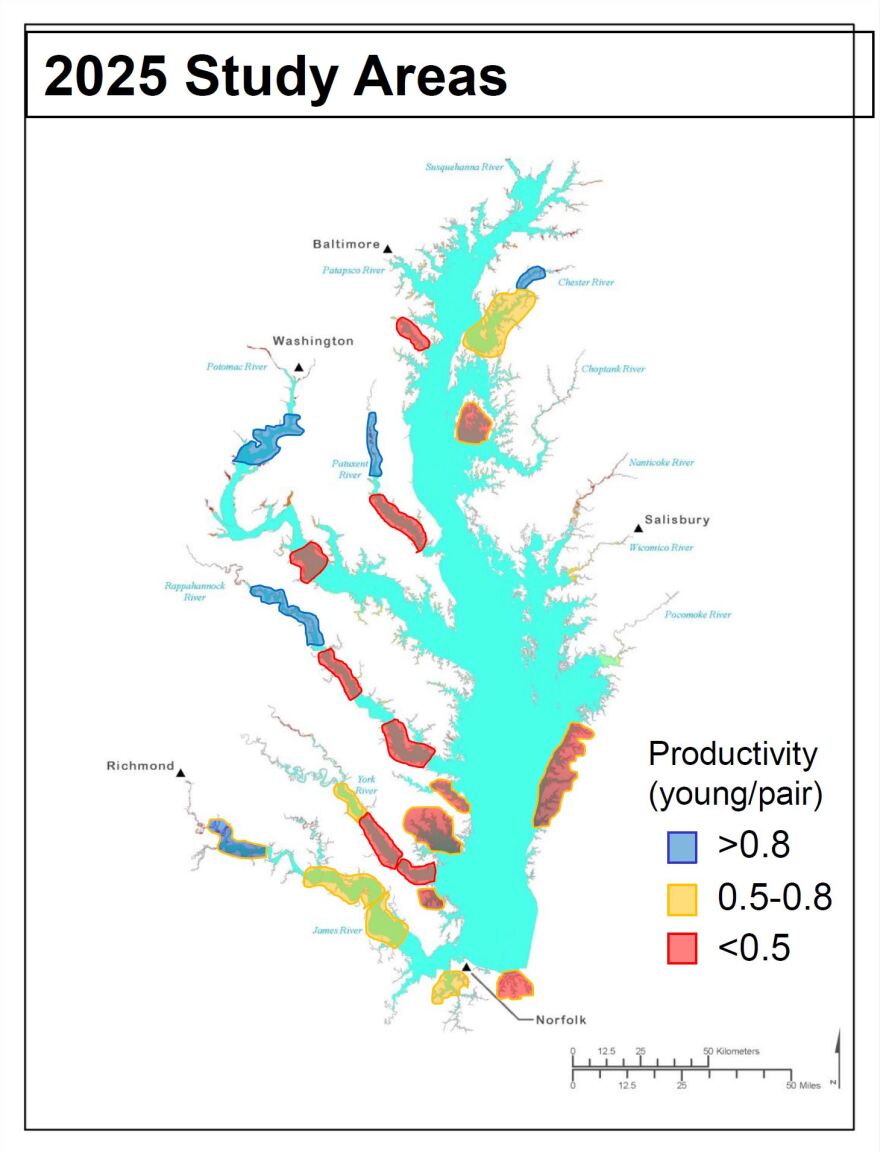

His team observed more than 1,000 osprey pairs at 23 sites throughout the bay and its tributaries.

The results show that ospreys are thriving in parts of the watershed with more freshwater – but not enough to compensate for likely losses in saltier areas, such as Hampton Roads. Watts says that’s because birds in these areas have different diets.

“No matter how you look at it, there just is not enough surplus to offset the deficit,” Watts said. “It is hard to imagine a scenario right now where the population will not decline.”

Researchers monitored osprey nests throughout the nesting season, which runs from March to August, to determine how successfully the birds are breeding. Fieldwork involves using mirrors mounted on poles to peer into nests.

The study areas were distributed across salinity levels. Areas in the lower bay, closer to the flow of the Atlantic Ocean, are saltiest.

“Saltwater comes in and circulates around the bay and is diluted as it gets closer to these freshwater sources” such as the Potomac and James Rivers, Watts said.

More than 80% of the bay’s surface area has at least a moderate level of salinity, he said.

The ospreys’ breeding performance closely adhered to those levels.

Osprey pairs need to produce an average of about 0.8 to 1.3 chicks per year to maintain a stable population.

In areas of the bay with the lowest amount of salt in the water, ospreys achieved that with an average of one chick per pair. Those areas were limited to the upper reaches of the James, Rappahannock, Potomac, Chester and Patuxent rivers.

The remaining 18 sites were not as successful, with ospreys in the saltiest areas producing an average of only 0.25 young per pair.

“I don't think osprey are going to disappear from the bay,” Watts said. “But if we continue on the road we're on right now, it's pretty clear that they will decline and disappear from certain parts of the bay.”

Salinity itself does not affect osprey, Watts said. He used it as a proxy for the kinds of fish in those areas, which are food for the birds. Catfish are more of a freshwater species, for example, with speckled trout preferring saltwater, he said.

Ospreys are the only birds of prey that eat almost exclusively fish, lending them the nickname of “fish hawks."

Watts believes ospreys in the saltier parts of the bay are struggling because they cannot find enough food to feed their chicks.

But the recent study simply provides more data. Many questions remain about the cause of declines – and that research has become controversial.

Watts previously conducted similar research on a smaller scale. First, he looked at ospreys in Mobjack Bay, where William & Mary has a long record of data to draw from.

Facing criticisms about the limitations of such a small study area, the team expanded last year’s survey to 11 sites in the watershed. This year’s goes to 23.

The controversy centers around the industrial harvesting of menhaden.

Recreational anglers and environmental groups have long pushed Virginia to ban the industry from the Chesapeake Bay, arguing that menhaden are disappearing and impacting the rest of the food chain, such as ospreys and striped bass.

The industry, meanwhile, maintains there is no evidence that menhaden are in decline or that the population is being overfished.

The Menhaden Fisheries Coalition has pointed to statements by scientists with the U.S. Geological Survey, which is also analyzing ospreys around the bay.

“It's important to keep in mind that there are many factors and stressors that can affect osprey reproduction,” Barnett Rattner with the USGS’ Eastern Ecological Science Center told members of a coastwide menhaden regulatory board last year.

That includes limited food availability, disease, changing climate conditions and water quality, he said.

Watts said his center focuses on observing ospreys, but that other entities should step in to figure out the cause, especially to connect or rule out the role of menhaden.

Virginia’s General Assembly has repeatedly declined to fund a deeper study of the local menhaden population, which could help settle the debate.

“We need to know in order to plan for the future,” Watts said. “The osprey, although they're only one consumer, have spoken pretty loudly at this point. Some people may choose not to listen.”