In a strip mall north of Richmond, it’s graduation day for a class of home care aides. The group stands up together to recite a creed.

“I will strive to maintain integrity and be strengthened by compassion, courage, and faith at all times,” they chant.

The group is diverse, a reflection of the workforce they’re about to enter. According to an analysis of census data Virginia home care workers are 86-percent female, 47-percent African-American, and 15-percent foreign born.

Related: Read the Rest of the Series on Home Healthcare

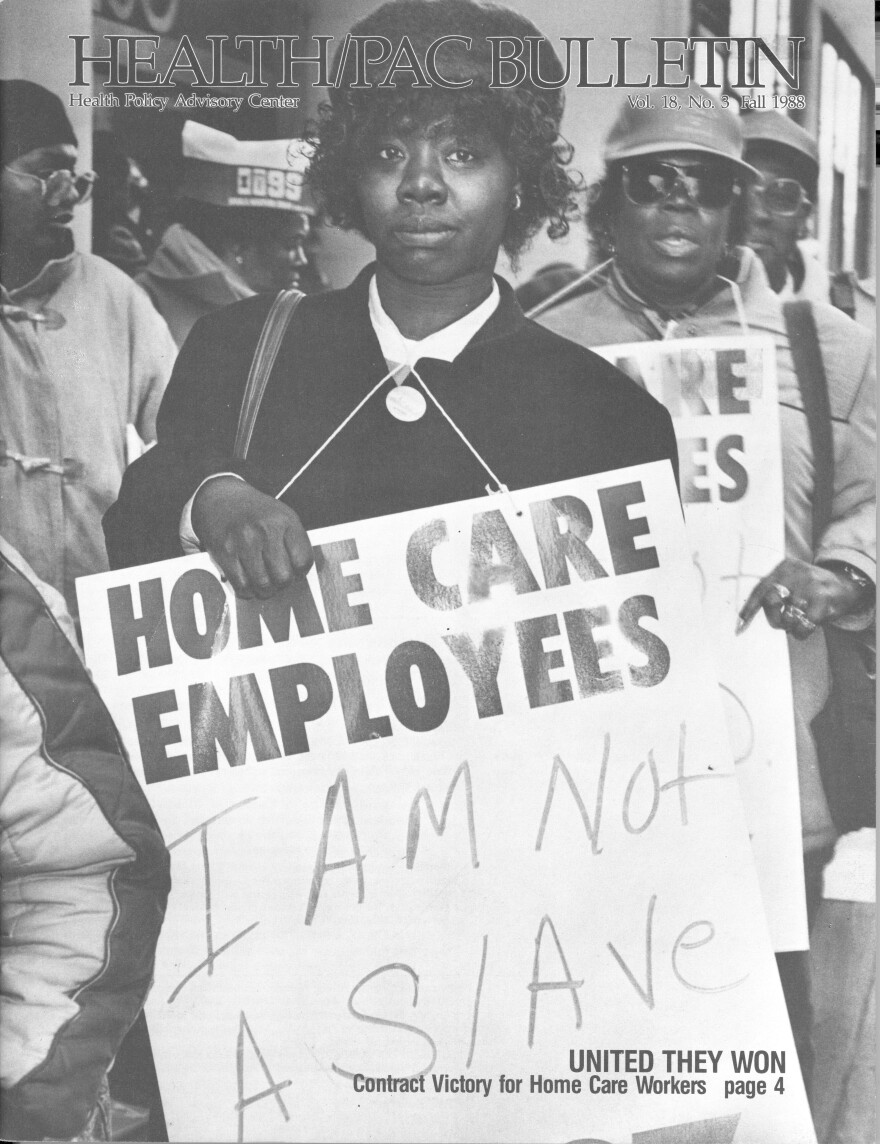

It’s no accident that women, and particularly women of color, are who we rely on to do this work. And that history has ramifications.

‘We Need Each Other’

Everyone graduating today is excited to begin a new career. They see it as a entry into healthcare, and a way to truly help people. But they’ll face challenges in this job. Pay is low and the profession is overlooked.

Related: The Underpaid and Overlooked Workforce that Cares for Virginia

Dawn Beninghove is running the graduation ceremony. Over the years, her business, Companion Extraordinaire, has trained about 600 personal care aides. Many have already experienced caring for a loved one.

“And they want to either be able to care for them appropriately now, or they want to change the world from what they saw happen to their loved one,” Beninghove explains.

Even Beninghove, a nurse who understands and believes in the importance of home care, admits aides are often looked down on.

“It’s so hard for people to see us, I believe, as a total team. That I need you. You need me. We need each other,” she says.

To understand where that disrespect comes from, and how it affects the people who do the work today, requires a dive into history.

“Why Would You Need to Pay for Such Work?

Home care work isn’t just looking after someone’s physical needs. Whether it’s a part of the job description or not, aides are often expected to cook, clean and perform other domestic service.

Labors that historically in America were performed by enslaved African-Americans, or later in history, black domestic servants.

Jennifer Klein, a history professor at Yale University, says that stigma of servitude carried well into the 20th century.

Klein and Eileen Boris, a professor at University of California Santa Barbara, co-wrote Caring for America: Home Health Workers in the Shadow of the Welfare State.

They point out that before home care became a formal occupation the duties of the job were -- and still are -- expected of wives, mothers and daughters.

“Why would you need to pay for such work? There’s a deep expectation that’s perpetuated through ideology that this labor should be given freely out love or marital obligation,” Klein says.

During the Great Depression home care was viewed as a form of workfare. A public works program provided the jobs to poor black women who would otherwise be collecting welfare.

The effort though, says Boris, was half-hearted.

“There was an irony in all this,” Boris says. “In having a racialized workforce of former domestic workers, and poor women on welfare, what was actually created was poor jobs.”

The jobs weren’t just poorly paid.

At the very moment that this job would become a formal occupation they get completely cut out of the minimum wage, the fair work week, any possibility of overtime.

During the same time period, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act -- sweeping legislation that guaranteed workers’ rights. Home care workers, along with other professions primarily done by African-Americans, were excluded.

"So at the very moment that this job would become a formal occupation they get completely cut out of the minimum wage, the fair work week, any possibility of overtime,” explains Klein.

Later, in the 1970’s, the FLSA was amended to rectify the racist exclusions. But, yet again, homecare workers were excluded. The profession was clumped with jobs like babysitting, and considered companion work.

“But this term companion had never existed before,” says Klein. “It was ruse that was pulled to cut them out of the expansion of labor rights.”

Why would lawmakers want to exclude home care workers from overtime pay and the minimum wage? Klein and Boris can’t say for sure, but they do point to the fact that long-term home care is primarily paid for by government dollars. And in the 70’s, that budget item was growing.

“And how are you doing to finance it? Without it taking over the whole budget? Well. Labor on the cheap,” explains Boris.

It wouldn’t be until 2015, through a bureaucratic rule change spearheaded by the Obama administration, that home care workers finally get labor protections.

"It All Goes Right Back Downtown to Richmond"

Today, three-quarters of home care is paid for through Medicaid and Medicare. Paying home care wages is a chunk in state budgets across the country.

When the Obama administration required home care workers be paid overtime compensation, state lawmakers across the country -- including here in Virginia -- responded by placing a 40-hour cap on billable hours.

“It all goes right back downtown to Richmond,” says homecare worker Thomasine Wilson.

In her twenty years of doing the work, Wilson has faced all sorts of “foolishness.”

We need legislation that will appreciate and respect the work that we do.

“I need this living room cleaned, the dining room cleaned, all the beds made, the floor scrubbed” she mimics. “Really? I don’t do that.”

What she does do is stand up for herself. In recent years she’s decided the best way to do that is to lobby the General Assembly.

“We need legislation that will appreciate and respect the work that we do,” Wilson says. “And give to the care provider that’s taking care of our elderly and making sure that their lives are pleasant to the end.”

In recent years state lawmakers have shot down proposals to give home care workers overtime and pay for additional training.

Lawmakers did approve a two-percent raise in the most recent budget. That would bring workers making $9.22 an hour, up to $9.40.

Catch up on other stories in the series here.