Virginia has a long affiliation with collegiate and minor league baseball. But for a number of years, others who played the game on the side found it was not only a way to take their mind off dangerous work, but also brought a sense of normalcy for coal mine workers in Southwest Virginia.

The ‘coal camp’ teams go all the way back to the early 1900’s, playing in towns like Coeburn, Dorchester, and St. Paul– but there were an endless number of teams, many near mines in neighboring states.

They became a spot for some future big-league talent, while others, whose pro careers were over, had a last chance to play before a crowd.

Writer Lynn Sutter stumbled across this history when moving to the area in the early 2000’s.

“I saw a photograph of a ragtag baseball team – they had the name ‘miners’ on their jerseys,” she says. “And some of the letters were sown on, and some of them were drawn on with a pen. And they did have coal dust on them, and I thought ‘oh my gosh, here’s this great juxtaposition of these guys doing the worst job in the world, and them coming out and putting on baseball uniforms.”

So Sutter started doing her research – and tracking down and doing interviews with players from the coal camp teams’ final years, in the late 1940’s and early 50’s.

“Amateur baseball back then was a big thing, semi-pro baseball,” said Terry Smith, who Sutter spoke to for her research. After serving in the Navy during World War II, he was a catcher for a team based in the town of Appalachia. “It was big – the merchants helping out, that was sort of advertising for us.”

Sutter said Appalachia was an incorporated community in the thick of probably a dozen coal camps. Around 2006, she talked to roughly 35 players for her book, ‘Ball, Bat, and Bitumen: A History of Coalfield Baseball in the Appalachian South.'

Smith and most others have since passed away.

“The predominating attitude towards Appalachia is that it’s this remote place where nobody ever goes and nobody ever leaves, and we are the yokels who command the mountains, and nothing else,” she explains. “But in minor league baseball, or even in coalfield baseball, people who would become very famous engaged in it.”

Sutter says these players were pretty competitive, to the level that a good many were offered minor league contracts – but the pros couldn’t pay nearly what the mines did.

Willie Winkles pitched for the Dorchester Cardinals mining team, and told Sutter he questioned his boss about larger paychecks.

“He said ‘I’m the time keeper, I’ll take care of it - and you pitch baseball. For a little over 3 years, I got time and a half for every Saturday. That was $27 dollars. That was big money back then,” he said.

Sutter says many of the players’ day jobs in the mines were determined by race. She says nearly all the Black players worked underground, while good ball players who were white, like Winkles, were hired solely for their skill on the diamond, and almost always worked above ground.

And Sutter says the teams themselves were segregated.

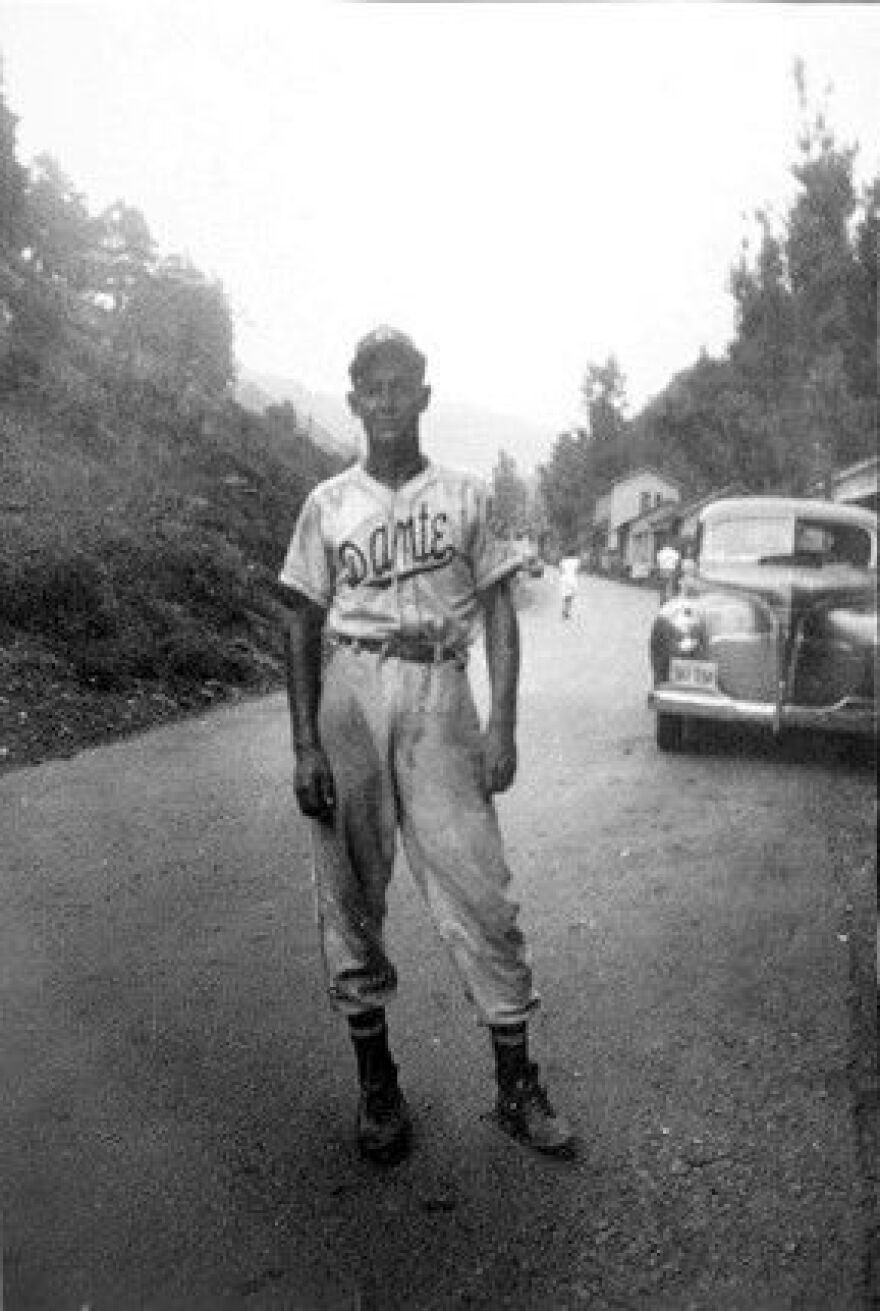

Theordius Miller pitched for an all-Black team, the Dante Bearcats. But he told Sutter the crowd in the stands was mixed.

Sutter: “Did you guys draw some of the white fans?

Miller: “Oh yeah, we had a whole heap of white people come to our game. I’d like to say we looked like one big happy family. They would come watch us, we’d go watch them.”

Among the best known players from the coalfield teams was Wise County native and Boston Red Sox pitcher Tracy Stallard. He was best known – perhaps unfairly – for one pitch, allowing New York Yankee Roger Maris to hit a then record-breaking 61st home run in 1961. It made Stallard famous, but Sutter says he grew tired of being asked about it. He died in 2017.

She believes the popularity of coalfield and minor league baseball waned as more people could watch major league games on TV in the later 50’s.

Sutter, who lives in Norton, says it takes some doing today to find evidence of the coal camp teams, as well as minor league clubs of the same area, but plans to talk to schools.

“I’d like for the young people who attend the local high school here – and who play ball on it – I’d like for them to understand the very same fields that they play on are basically located where the Class D Mountain States Field League field was located in Norton,” says Sutter.

Norton also gained noted notoriety for integrating Little League baseball in the South in 1951. In June, a historical marker was unveiled.

Leeman Field, in Pennington Gap, built in 1933 was one of the last minor league fields with no outfield fences. It hosted many minor league games, but also coal field teams from time to time. It’s now a local recreation site and greenway.

There are no historical markers, but Pennington Gap Town Council member Terry Pope says “that would be a nice designation.’

Sutter’s 2008 book on the coal camp teams was honored with a SABR award- from the Society for American Baseball Research. Her work can also be found in print and online in the Coalfield Progress newspaper. Her follow-up book, “New Mexico Baseball: Miners, Outlaws, Indians and Isotopes, 1880 to the Present," also earned her SABR honors in 2011.

“I think that the only way that the overall story can be enlarged upon is through nuggets that people can send to me, and tell me stories, and indeed they’ve started doing that."