Rapidan is one of those scenic little towns in the Piedmont, lush and green, with three churches, an historic graveyard and an old mill along the river, powered by a dam which has been in that space for nearly 250 years.

Nathan Marshall, who grew up in the area, says during the Civil War General Lee’s men camped on one side of the river, Northern troops on the other, and they met in the middle to be baptized.

“There is an account from the diary entries of a pastor who led that congregation. He baptized 17 souls – Johnny Reb and Billy Yank down in the river bottom attending a baptismal service together.”

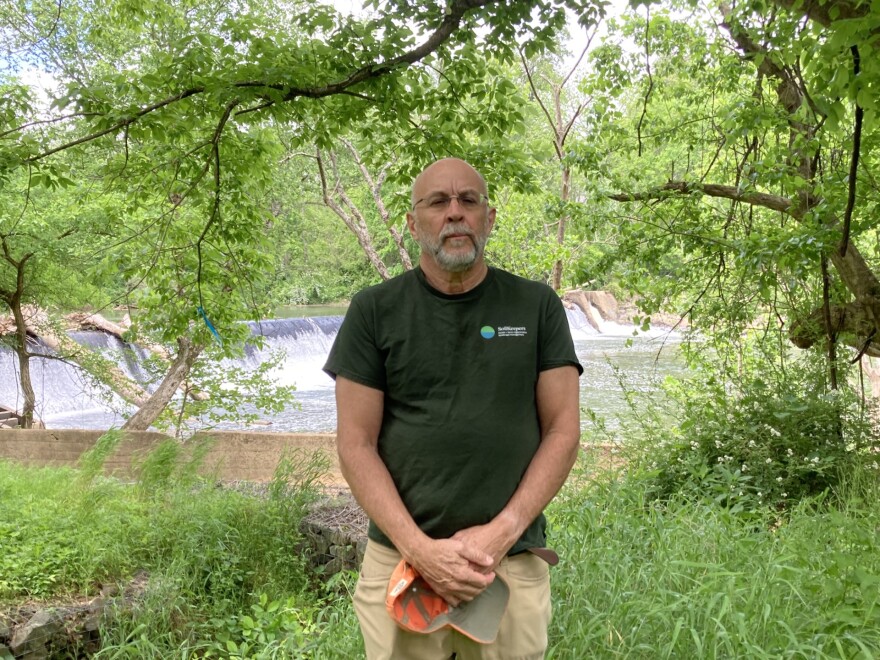

The river flows from the Blue Ridge Mountains to the Rappahannock and on to the Chesapeake Bay. Michael Collins, with American Climate Partners, says Rapidan was one of four mills built on its banks.

“Liberty Mill, Spicer’s Mill, Madison Mill and Rapidan Mill, and this is the last remaining dam.”

He and several other environmentalists have spent the last five years trying to figure out how they could remove the dam and restore populations of herring and shad— what one historian called the Founding Fish.

“At the time of the American Revolution they were a staple. There’s even a story that they saved Washington’s troops when they were starving. they were so plentiful that it felt like you could walk across their backs when you went across the river.”

But those fish have been in decline ever since – victims of water pollution, overfishing and barrier dams that keep them from reaching the full potential of their spawning habitat. Again, Michael Collins.

“There’s somewhere between 500 and 1,000 miles of spawning habitat behind this structure. That is why American Rivers says this is one of the most significant dam removal projects.”

The non-profit American Climate Partners actually bought the dam and got a grant from the federal government to remove it.

They were poised to start the project when worried residents began raising concerns. Andy Hutchison, who has lived in the area for 53 years, worried about invasive blue catfish and Northern snakehead, populations that have exploded in the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries.

“I’m not a biologist," he says, "but I think common sense would indicate that if those things are invasive and they’re voracious feeders of rockfish, shad, herring and crabs, then why would you give them more habitat to expand into.”

Others wondered if people living on the banks of the Rapidan might see increased flooding.

So, Collins and his colleagues invited the public to a three-hour program at Orange County High School where nine experts answered questions. Adam Schellhammer with the advocacy group American Rivers, said removing dams usually reduces the risk of flooding.

“When you think about Hurricane Helene that ripped through Ashville, there were a couple of dams we were worried about the risk of failure. That’s a wall of water and sediment and debris running all at once," he explains. "Part of what we can do with a managed project is ensure that we deal with the sediment and that wall is not going to come down in the next storm event.”

Where dams are taken down, he says, water quality improves as rapid flow increases oxygenation, and as the river narrows, some properties are removed from 100-year flood plains, increasing their value.

John Odenkirk, with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, doubts invasive fish will be a problem given the state’s experience with removing another dam on the Rappahannock.

“They didn’t really expand in that little reach where they had access," he recalls. "Why? Well because the habitat was not to their liking. It was very high velocity, boulders, cobble. It wasn’t that soft, mucky bottom, that easy tidal influence.”

What we have seen in other cases, he adds, is that getting rid of dams boosts native fish populations and provides easier river access and safer conditions for people who enjoy fishing and boating.

Special thanks to Hilary Holladay at Byrd Street for her assistance in preparing this report.