When individuals lose their health insurance, it most directly affects them and their families. But when a lot of people lose their health insurance at the same time, the impact can be felt across an entire community.

Last year, Tennessee dropped some 200,000 people from TennCare, its health care plan for the poor and uninsured, and reduced benefits for hundreds of thousands more. The impact is being felt in places like Cocke County, one of the state's poorest.

Trying to Get By Without Care

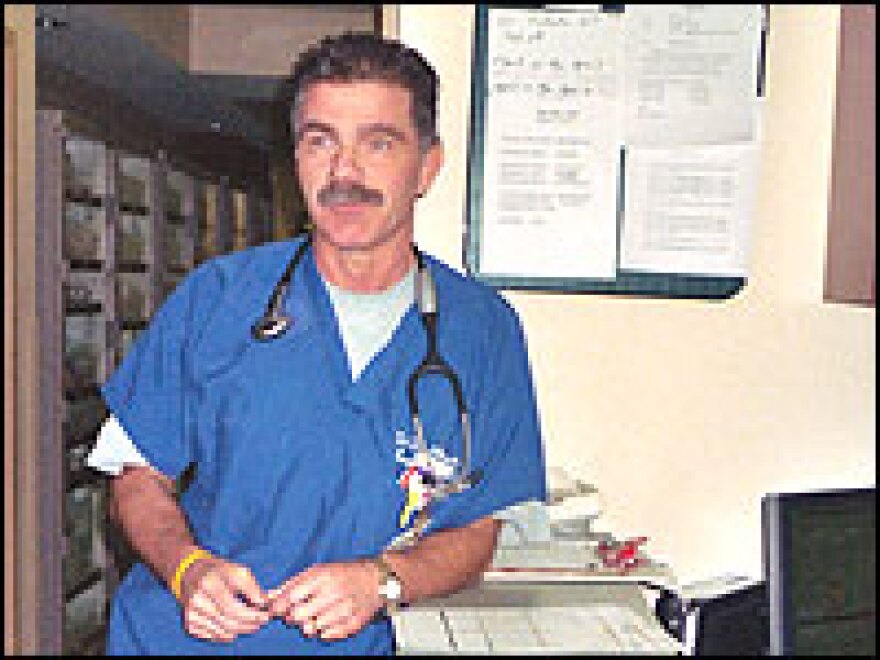

A little before 8 a.m. in the gleaming new emergency room at Baptist Hospital of Cocke County, Dr. Constantino Diaz-Miranda is seeing his first patient.

"My goodness gracious! I'm Dr. Diaz. What's going on?" he asks Ruth Evelyn Whaley. Whaley fell and jammed her hip a few days earlier, but now the pain has worsened.

"What was the reason that you didn't get your medicines -- you were saying?" Diaz asks.

She tells him, "I didn't have no money to pay for them."

Diaz says it's becoming an increasingly common storyline in this part of the state. By some accounts, as much as 40 percent of Cocke County residents were on TennCare before the cuts.

Now, patients who have lost their coverage try to get by without care, until they simply can't wait any longer.

"I have had patients that were quite sick because their insurance was not in effect any longer, and they do not have the ability to buy the medicines," Diaz says.

An Insidious Growth in ER Visits

Diaz, who speaks English with a thick accent, moved to Eastern Tennessee from Spain two decades ago to do his medical residency -- and never left. He says when the TennCare cuts happened, many expected an immediate surge in uninsured patients showing up in the ER. That didn't happen.

Instead, the growth has been more insidious.

"It's happening slowly," he says during a brief lull between patients. "I've been here long enough that I have lots of recurring patients. And I know in the past they have had TennCare. And today they are listed as private pay -- in other words, no insurance. You know, little by little it's happening, and it's getting worse."

Some of the patients show up at the hospital because without insurance, they can't afford to see their primary-care doctors anymore. "They have to come up with $25 or $50, whatever, that the office will charge them to be seen. We see quite a few of those," he says.

Untreated Chronic Disease

In other cases, patients with chronic ailments simply try to do without -- until they actually do need emergency care. Diaz says one woman with diabetes who'd lost her insurance was a repeat visitor.

"When I saw her, it was her third visit to the ER with blood sugar in the 600 to 700 range." That's dangerously high.

In the end, Diaz simply dug into his own pocket to get her what she needed.

"If she went back to the house without any insulin, she would come back the next day," he explains with a shrug. "So we bought her the insulin and got somebody to draw the insulin out of the bottle so she would get the right dose."

And is it getting to the point where the whole thing just falls apart?

"We are not there yet," he says, "but I believe that if this continues this way, we will get there -- unless the state comes up with some sort of program where they can help more of those patients where they don't have no insurance."

Ripple Effect

The increase in uninsured patients is big a worry for Baptist Hospital Administrator Jim Decker. Just two years ago, the hospital spent millions of dollars to expand its emergency department from seven to 17 beds.

But it's not clear how the hospital can pay its bills if its patients can't pay theirs. And Decker says that could cause a ripple effect of its own.

"Quite often, the hospital is one of the foundations, the institutions of any community. And that's certainly true here," Decker says. "We're one of the largest employers. It's an important component of this community, and one which we're trying hard to maintain."

Food or Medicine?

Across the street from the hospital and around a winding gravel driveway is the local food pantry, called the Bread Basket.

Linda Owens is one of many volunteers who has also been a recipient. She says she's seen demand for not just food, but for other services pick up since last year's TennCare cuts. Owens, who also operates a separate ministry that distributes household goods to the community's needy, says people are having to choose between buying food or medicine.

She says the cuts in health care have had a negative effect on more than just people's health.

"It increases our theft rate, because people are having to survive," Owens says. "If you know you don't have a drug that's going to keep you alive, that puts your family in a position that they're having to make choices they shouldn't have to make. Some have chosen to sell their food stamps -- which is illegal. But they've had to do it to get the medicine to keep them alive."

Feeding the Cycle of Poverty

Phil Ruch oversees operations at the Bread Basket. He carries a tally book that shows how demand at the bread basket has spiked since last year's TennCare cuts. Ruch, who also works as a nurse at the hospital across the street, says he's not at all surprised by the connection between the two events.

"We have a sign we take to fairs that describes the cycle of poverty," he says. "One of the elements of the cycle of poverty is poor health care. Because folks don't have access to the medical care that they need, because of that they also get sick. Because they get sick they can't hold a job. So all of that impacts the total picture."

And it's not just charities feeling the impact. Local businesses have been affected by the TennCare cuts as well. Down the hill from the hospital, just across from the railroad tracks, is Wilson's Sav-Mor pharmacy. Marty Bailey is the owner and pharmacist.

He's been there 23 years. But business hasn't been so good since the TennCare cuts.

"We had to lose 20 to 30 percent of our business when TennCare changed," he says. "We had to cut down dramatically on our prescription-drug buying. We have had to cut back on the hours of our employees, because you don't know if you're going to be able to pay the bills next month."

'Which One Are They Going to Die of Quickest?'

You hear a similar story just up the street at Jabo's pharmacy. In front is an old fashioned soda-fountain. It's crowded with workers from the Con-Agra canned-food factory next door, many still wearing their hair-nets.

But the 1950s-era front of the store contrasts dramatically with the scene behind Jabo's pharmacy counter. There, busy clerks stand in front of computer monitors, while a huge counting machine sorts pills and spits them out neatly in bottles.

Jeremey Sherrod is one of the pharmacists. He says the last few months have been particularly difficult, especially for the TennCare patients who've had to cut back on their prescriptions.

"You know it's hard to tell them whether to treat their diabetes or their congestive heart failure. Which one are they going to die of the quickest if they don't take their medication? It's like we're making the decision of life and death in a sense, and we're not meant to do that," he says.

Sherrod says he worries most about the people who come from some of the more remote areas in the foothills of the Great Smoky mountains. He says when they encounter problems at the pharmacy counter, they're as likely as not just to go home.

"Obviously, in a rural community where there's less education, less jobs available, where the people are less aggressive to fight for their rights, it's going to make a larger impact than it would in a more suburban area," he says. In Cocke County, "the people just accept it and say 'Hey, if we can't get it, we'll go on without it. if we live, we live. If we die, we die.'"

Just last week, Tennessee Gov. Phil Bredesen signed into law a new program that would subsidize private insurance for low-income working families. But most of those who were dropped from TennCare last year won't be eligible. And it's not yet clear how much the new program will help boost the fortunes of the people of Cocke County.

Produced by NPR's Rebecca Davis.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.