When the pandemic hit, staff at the Wildlife Center of Virginia figured they were in for a quiet time. In fact, the last year turned out to be the busiest ever, with more than 3,700 animals coming in for care.

It’s spring – which means baby birds are hatching, and – sometimes – falling from their nests. Experts say people who find them should put young birds back, but if that’s not possible, it’s time for a call.

“Wildlife Center of Virginia, this is Lonnie. How can I help you?”

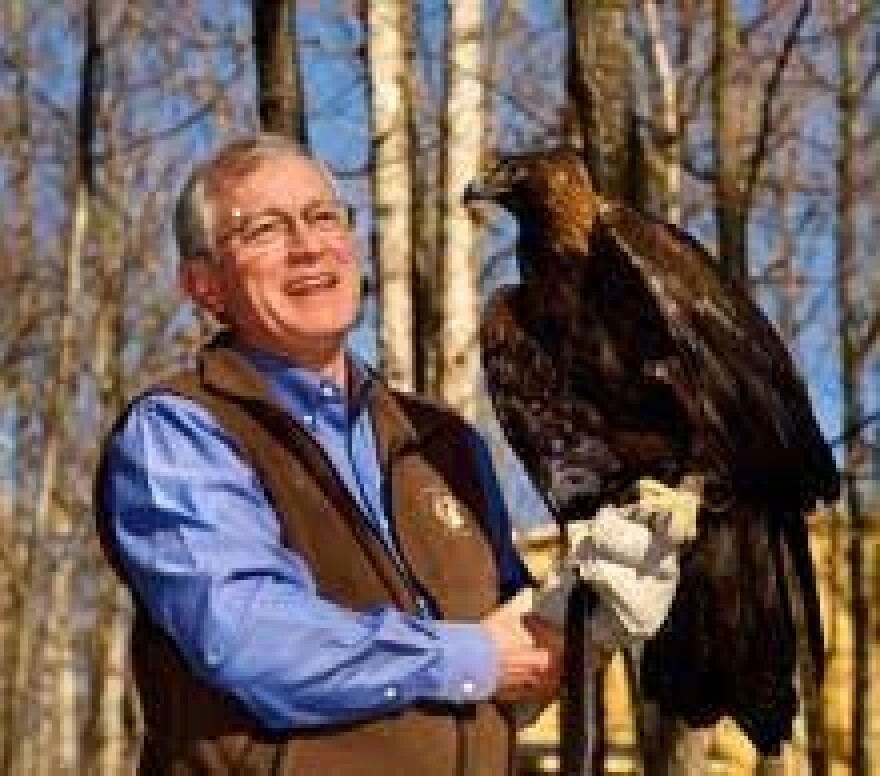

The Wildlife Center of Virginia is perhaps the busiest place in the state right now, with people calling from all over the Commonwealth. Founder and president Ed Clark says the pandemic prompted many to spend time outdoors.

“Finding more animals, baby animals around their yards. They were hiking in the woods, and the opportunity to pick that animal up and bring it to the wildlife center was probably the least boring thing they had done in a month,” Clark recalls.

But, he says, animals that are not injured may not need the assistance of this state-of-the art veterinary center. Young owls, for example, may fall out of trees before they can fly, but they’re actually able to climb back up to their nest according to chief veterinarian Karra Pierce.

“Once their primary feathers are grown out enough, they can actually climb vertically up a tree using their feet, their beak and flapping their wings really hard,” she explains.

And at the front desk, Lauren Swinson advises a caller not to bring baby bunnies in for care, even though their nest was exposed by someone mowing a lawn.

“Okay, so there is a way to tell for sure whether or not the mom is coming back to that nest," she says to a caller. "Take some string and do a tic tac toe pattern over the entrance of the nest, and then you’re going to want to give it through the next morning, and if that pattern has been disturbed it means the mom has come back to nurse the babies, because they only nurse at dawn and dusk. If it hasn’t been disturbed then that means she’s probably not come back, and then he would need to proceed with finding a licensed rehabilitator to care for those rabbits.”

There are about 300 people around the state who’ve been trained to care for orphaned baby animals or injured wildlife, and the center often refers callers to them.

“I do rescues, transports, and I’m a category one rehabber,” says Bernadette Ames, a retired teacher from Williamsburg, who drove two hours to deliver an injured red-tailed hawk and a great horned owl. She loves caring for wildlife and feels called to do it.

“ We need to take care of them, because we’re taking over their land, and they’re just being pushed and pushed," she says. "You know these highways, they can’t even cross without getting hit, so yes, I really love it. I get such a joy.”

Several baby owls have arrived this spring, screeching to be fed every two hours. Shannon Mazurowski is one of four wildlife rehabilitators at the center.

“Today I started my day at 7," she recalls. "I fed baby vultures, baby barred owls, squirrels, possums, cottontails and a few songbird babies and our black bear cubs.”

Each animal poses a special challenge. The owls, for example, must not be exposed to people. Early in life they learn to identify with whatever they see according to veterinarian Pierce.

“We wear basically camouflage. We try to be invisible to them so they don’t get used to humans, and we’re completely silent. There are big signs all around the back where we have babies – absolutely no talking! Babies inside.”

For more on the process, click on part two below:

Last year, 3,700 animals were treated at the Wildlife Center of Virginia – a high-tech veterinary hospital caring for creatures brought in from all over the state. In part two of our series, Sandy Hausman reports on how baby animals are raised so they can return to the wild.

Baby bears actually purr when they’re content – after a bottle of formula, for example. Hundreds of orphaned cubs have been fed over the years at the Wildlife Center of Virginia where rehabilitator Shannon Mazurowski works.

“We generally keep them for about a year or a little over, because that’s how long they would stay with their mothers,” she explains.

They’re cute, and they look cuddly, but once they’re weaned the staff will have minimal contact with bears. The center’s president, Ed Clark, says they are kept in a specially designed enclosure and rarely see people.

“Bears habituate very easily, and the cases when we’ve had the conservation police bring in a cub that somebody’s had as an illegal pet or try to turn into a pet, if they’ve had even a few days or a week, the chances of that cub completely developing a wariness of humans is dramatically reduced,, and we could not release them.”

Today, the center will release the last of 21 bears it raised over the last 15 or 16 months. They an weigh up to 150 pounds, an head veterinarian Karra Pierce says getting them ready to go is hard work.

“They’re big black bears now. They have to be fully anesthetized in order for us to move them, to work on them, do a physical exam, make sure they’re healthy, switch out their ear tags, do some blood work on them, and the Department of Natural Resources comes and drives them back to the world and lets them go. “

They’re released in wildlife management areas all over the state, to places chosen by bear biologists in each area.

When they’re first offered their freedom, these two bears seem wary – studying the neighborhood before jumping from the truck and rushing into the woods. They linger there, studying the trees – as if amazed by the sheer number of places to climb.

The Wildlife Center also finds it challenging to care for baby owls. Here again is veterinarian Karra Pierce.

“They’re very cute, but they’re hard to raise, because they are really at high risk for imprinting, so they need to basically see their mom or their dad to learn, ‘Oh, I’m an owl.’ So we’ve been working really hard lately to re-nest those patients when they come in.”

They’ll even create a new nest if the original has fallen down -- then watch to see if the mother comes back. If not, they’ll call on and older owl -- Papa G-Ho. He’s got a bad wing, so he’s been living at the center for years. He can’t go back to the wild, but he can serve as a surrogate parent.

“They sit next to him, and it’s kind of fun to watch them actually," Pierce says. "They are more curious and active than you would think. They hop around, and they tear stuff apart, but mainly he’s showing them how to be appropriately fearful of us and how to recognize their own species, so that when they’re released they can mate with the appropriate species and not view humans as them.”

Of course there’s always a chance that these animals treated and released to the wild will be killed by a car or a hunter. How the center thinks about that problem, and what it’s doing to help people co-exist with wild animals next week.