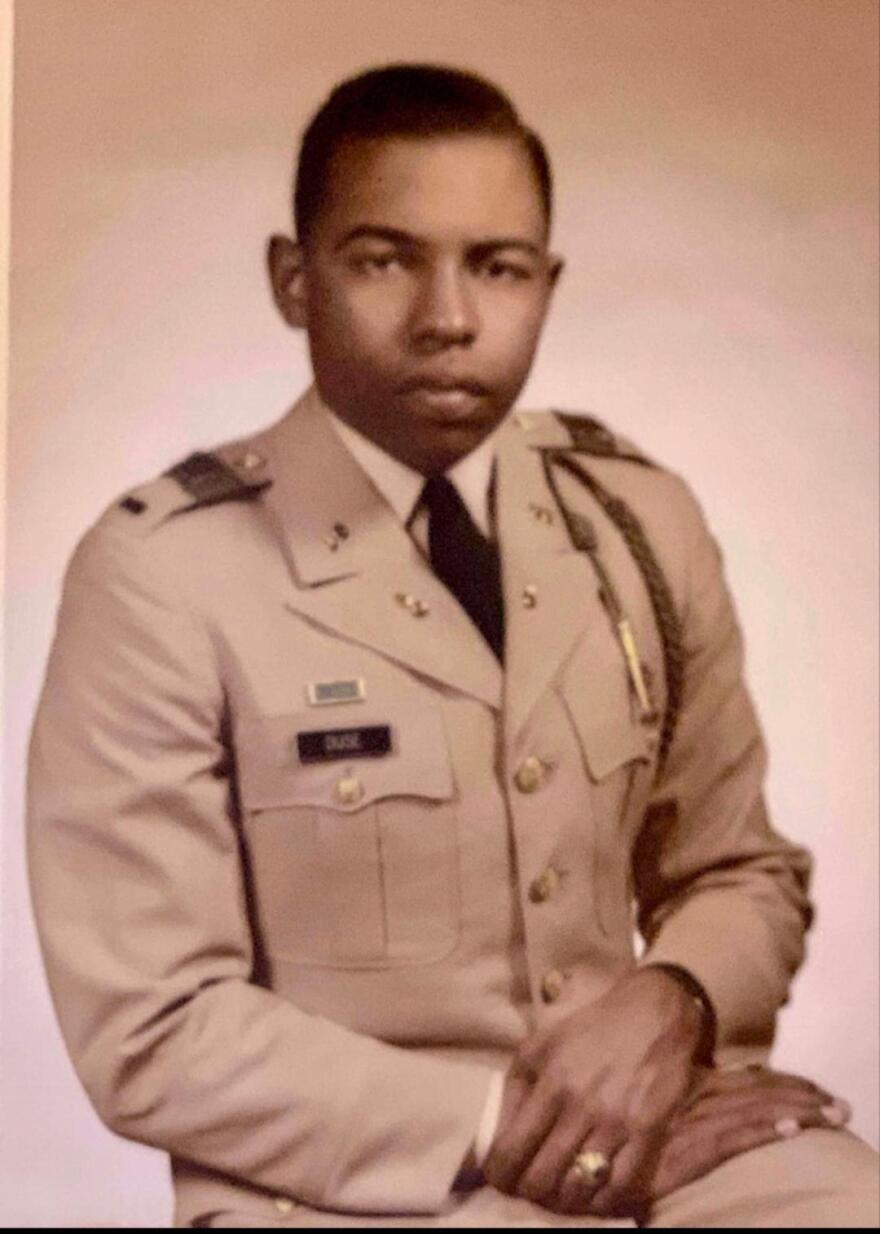

On paper, Bernard Duse seemed an unlikely killer -- a 76-year-old Black man with no criminal record, honorable service in the military, an MBA from Harvard and a string of jobs with Fortune 500 companies. He was married and still working as an assistant manager for CVS.

But his boss was shot and killed in an alley behind the store, and an all-white jury convicted Duse of the crime.

“They think he’s a murderer, but we don’t see him as that," says Karen Morrison with Fighting4Freedom – a non-profit she set up to help people she thinks might be innocent.

Duse’s niece, Lory Dance, was shocked when her uncle was charged.

“Shocked, confused. The eyewitness – the person who witnessed the murder – saw a white guy – said several times, ‘He was a white guy.’”

The prosecutor argued that Duse blamed his manager for costing him a promotion, and a lawsuit Duse filed against CVS for age discrimination was dismissed six weeks before the crime.

Cell tower records showed two phones belonging to the victim and the suspect traveled together after the murder, towards the suspect’s home, but Duse claimed he had left his phone in his car and lent it to a couple of acquaintances who knew about his treatment at work and might have killed his manager.

Duse’s niece is a professor of sociology at the University of Nebraska. She sat through the trial and claims the prosecutor was selective in presenting information. Duse had, for example, sued a previous employer – IBM -- for discrimination. The company hired a psychiatrist who concluded Duse was obsessive-compulsive with features of a paranoid personality disorder. That diagnosis was reported in the criminal case against Duse. Dance said her uncle had worked at IBM for 14 years and received excellent evaluations.

“It was very difficult seeing how he was being painted – how details were dropped out. How the prosecutor engaged in confirmation bias," she recalls. "The sociologist in me was really worried. The niece was less worried, because I knew my uncle was innocent.”

Duse was sentenced to life in prison. He is now 84 – suffering from terminal heart and kidney disease at the Deerfield Correctional Center. Again, his niece Lory Dance.

“My prayer is if he could just be home for one night and not die in prison.”

And advocate Karen Morrison argues prison inmates should have access to hospice care.

“The Department of Corrections does not have the means or the compassion to take care of our elderly or our dying prison population.”

So she applied for a medical pardon that allows the state to free someone if a physician believes they will die in the next 90 days. The parole board, which considers such requests, moved quickly to complete the paperwork and Dance was hopeful her uncle could die in peace at home.

“There was a house visit. It was approved. There were papers to be signed, with his wife saying she could take care of him and was aware of his health challenges.”

But after the Fourth of July weekend, Morrison got a short, unsigned letter from the governor’s office stating the pardon petition had been denied. Recalling the speedy pardon issued earlier this year for a Fairfax police officer who shot and killed a Black man for allegedly shoplifting, she has one question for Glenn Youngkin.

“The conviction came in Friday for the police officer Wesley Shiflett. You brought your staff in on a Sunday to grant his pardon, and Mr. Shiflett walked out of jail in two days, but here it is you have a man who served his country honorably and has no previous criminal record and you could not show compassion or mercy for this man.”

In its letter to Morrison, the governor’s office said simply – there is no right to appeal.