The osprey population along an important habitat corridor in Virginia is nearing “complete collapse,” local researchers reported recently.

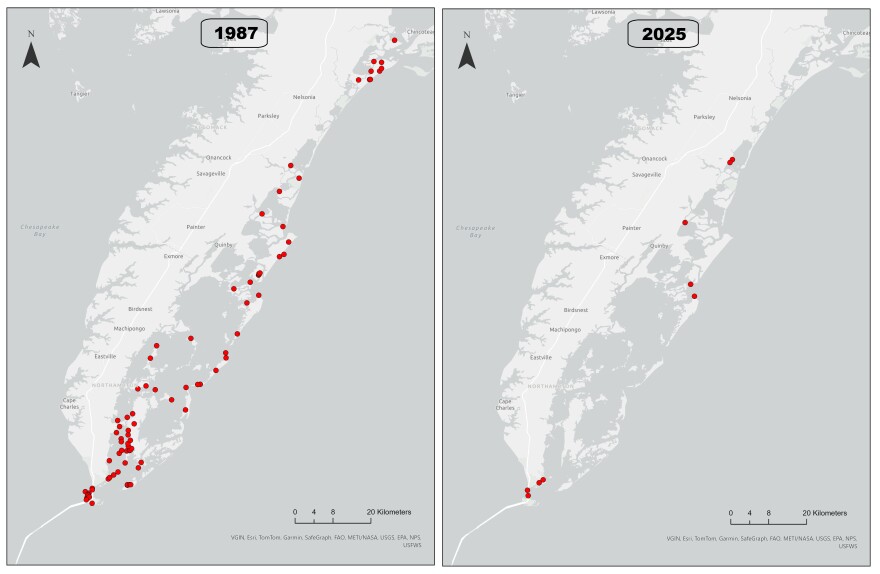

An annual survey by William & Mary’s Center for Conservation Biology found only nine pairs of ospreys living along the seaside of the Eastern Shore, from Chincoteague south to the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel.

That’s a decline of almost 90% since benchmark surveys began in 1987.

“Beginning in the late 1990s, we have observed an ongoing loss of pairs from structures that were used consistently for nesting over the previous 25 years,” Professor Bryan Watts, director of the center, wrote in a news release.

“The number of vacant territories has grown over time with many having been lost over the past decade.”

Historically, the Chesapeake Bay supported the world’s largest concentration of breeding ospreys, according to the Virginia Institute of Marine Science.

There are reports from 1875 of “around 50” osprey nests just on Hog Island, one of Virginia’s barrier islands east of the mainland, as well as several within the middle section of nearby Mockhorn Island.

“The number of osprey pairs supported by this area during pristine times must have been tremendous,” Watts wrote.

Bird experts refer to the 1970s as the height of the “DDT era,” when the widely used pesticides suppressed osprey hatching.

The 1987 survey that found 166 ospreys living on the Shore’s seaside suggested an ongoing recovery, Watts wrote.

But in the 2000s, the population started going “underwater,” he previously told WHRO. “And that’s continued to get worse.”

Researchers say the seaside of the Eastern Shore is an “internationally important area” for many migratory and resident bird species.

It’s not yet clear what’s driving the decline of osprey there. One contributor could be the rebound of bald eagles, which often steal food from osprey nests.

Watts thinks it’s more likely that there are fewer fish available for the birds to eat.

Ospreys are the only birds of prey to eat almost exclusively live fish, lending them the nickname “fish hawks.” They can dive feet first into water when hunting and get soaked “head to talon.”

In Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay, a majority of the osprey’s diet is made up of menhaden, a small, nutrient-dense fish.

Watts believes that overall declines of the osprey population in the bay – separate from the seaside area surveyed most recently – are linked to industrial harvesting of menhaden.

Virginia is the last East Coast state to allow the menhaden fishery in state waters. Environmental groups and recreational anglers have unsuccessfully pushed the state to ban the industry specifically in the bay, at least until researchers can learn more about the status of the fish.

Watts’ research on ospreys’ ties to menhaden has been hotly debated because of the ongoing fight between the menhaden fishery and its critics.

The Menhaden Fisheries Coalition, which represents the industry, released a statement this week in response to the latest findings, stating that the reduction fishery does not operate along the Shore’s seaside.

“We do not dispute Dr. Watts’ observations, but would like to be clear that if there is a prey availability issue, it is not being caused by menhaden harvesters because we simply haven’t been there,” the coalition said. “Osprey population dynamics are complex and worth understanding, and as federal researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey have described, multiple ecological factors—not a single fish species—are influencing osprey trends.”