Laura Mae fell in love with birds about a decade ago. She noticed them in the world around her, such as a rare pair of breeding peregrine falcons she watches nest every year in downtown Norfolk.

“Birds have just become my favorite,” she said. “I bird morning, noon and night. I dream about birds.”

Mae, who lives in Chesapeake, also participates in the annual Christmas Bird Count, which is considered the nation’s longest-running community science project.

The National Audubon Society launched the count on Christmas Day in 1900 amid concerns about declining bird populations.

Researchers, wildlife officials and other interested people use the information to monitor the long-term health of the creatures.

“It provides a picture of how the continent's bird populations have changed in time and space over the past hundred years,” the Audubon Society states on its website.

Last month, several Christmas counts were held in southeastern Virginia, including Williamsburg and the Middle Peninsula.

Mae helped lead the effort at the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge in Chesapeake and Suffolk.

She and about two dozen other volunteers rose before dawn on Dec. 14 and braved icy conditions.

“We had rain, then sleet, then snow that day,” she said.

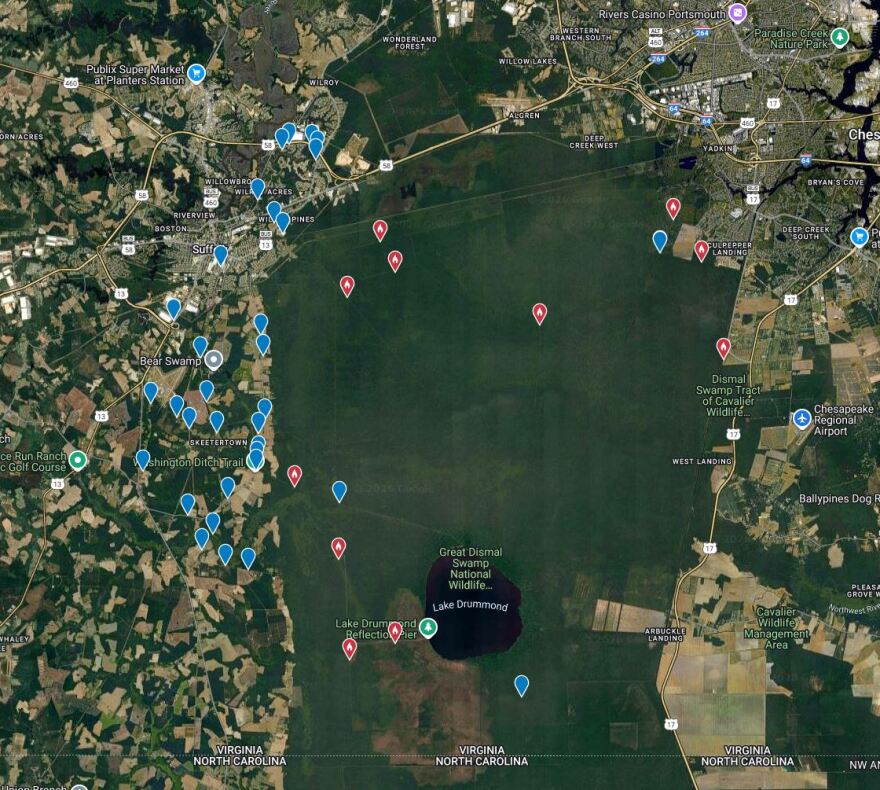

Volunteers divided into groups to cover 15-mile-wide circles across the study area, which includes much of the refuge and adjoining neighborhoods.

More experienced birders often use a pen and paper to note what they see. Others, including Mae, turn to a community science phone app called eBird, which is run by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

The app suggests birds people might see based on their phone’s location and allows users to form checklists and easily tap the right species when they see it, she said.

The results are in. Counters spotted more than 21,000 birds at the swamp, across 77 species. Plus, a bobcat.

The most common were American robins, common grackles, brown-headed cowbirds, red-winged blackbirds and tree swallows. Rarer finds included a northern harrier and a few orange-crowned warblers.

Bird populations have plummeted across the U.S. because of stressors such as habitat loss and extreme weather fueled by climate change. A landmark 2019 study reported a loss of 3 billion birds in North America over the previous half-century.

Mae said she hasn’t noticed declines at the Dismal Swamp, perhaps because of its role as an avian haven.

“When you look at the East Coast, the Great Dismal Swamp is one of the biggest patches of land,” she said. “So when you think about migrating birds, it's a really important place for them to stop. As a bird watcher, if you know when to be there, you can see really interesting birds.”

She’s traveled all over the world, including Africa, South America and Antarctica. But the Dismal Swamp remains one of her favorite places.

“Any time that I get to spend in there is a treasure.”

People can help protect birds by turning off lights at night or using window coverings to prevent birds from getting disoriented and flying into glass. It also helps to keep cats indoors.