Earlier this fall, the Executive Secretary of the Supreme Court of Virginia stood before lawmakers pleading. He was asking for more money so courts across the state could hire more clerks.

According to his office, more than half of the state’s district courts are under-staffed. That includes large counties like Fairfax, Chesapeake and Henrico - but also smaller courts in Smyth, Carroll and Rockingham Counties.

If staffing levels aren’t brought up mistakes could be made, impacting everything from people’s credit to jail-time. And if the issue isn’t addressed, courts may even have to shorten hours on customer service windows. That would make it more difficult for Virginians to pay fines or file cases.

Here’s a look at what more that could mean for the roughly 3.5 million cases that go through Virginia’s district courts each year.

The Impacts

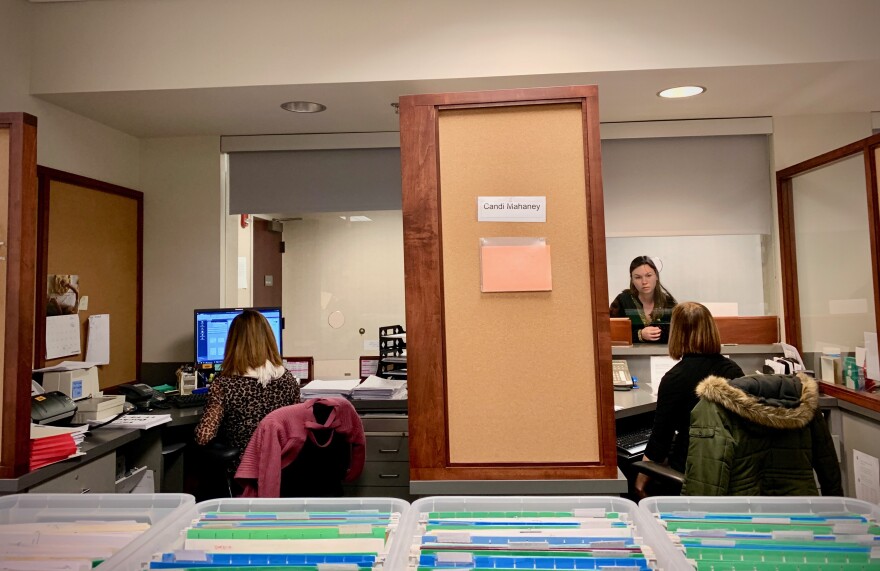

If you’ve ever been in a courtroom, you’ve seen a court clerk. They’re almost always up at the bench, sitting beside the judge. Clerks answer the phones, staff the customer service desks, and do all the behind-the-scenes work that allows the judicial branch to function.

“It’s becoming increasingly difficult for them to stay up, get the work done, do it without making mistakes,” said Karl Hade, Executive Secretary of Virginia’s Supreme Court. “And those mistakes impact people’s lives.”

Chesterfield County’s Juvenile and Domestic Relations District Court has 23 clerks. But they need more to handle the 40,000 cases a year they process. Clerk of Court Laura Griffin says those cases include child custody, visitation, child and spousal support.

“We see some of the most vulnerable people in our communities,” said Griffin.

The biggest impact of being short-staffed is a backlog. There are simply not enough hands to physically enter a case into the system and get it on the docket.

"It's becoming increasingly difficult for them to stay up, get the work done, do it without making mistakes. And those mistakes impact people's lives."

Across the state, delays like that can impact people’s credit and wage garnishments. It can even mean someone’s held in jail longer than they should be.

At the Juvenile and Domestic Relations courts the impact is on kids and parents.

During a recent tour of the court, Griffin pulled out a case sitting in the backlog. A guardian is owed $944 dollars in child support. They’re requesting a judge step in.

It could be months before that case is heard by a judge.

“Knowing that you’re working 50, 60 hours a week and you’re still not fixing some of the problems, it can be demoralizing," said Griffin.

This workload takes a toll on the women that do it (the clerk workforce in Virginia is 95% female.) In a recent statewide survey by the Supreme Court’s office, clerks say they work long uncompensated hours, that the job is stressful, and that it impacts their relationships.

For instance, another case sitting in the backlog is for a guardian who wants to be relieved of custody for a child in their care. Karl Hade says hearing cases like that can cause secondary trauma for clerks.

“I’ve had to talk to a parent that’s come to the counter with the child they desire to be relieved of, and look at that child’s face while his parent told me that we need to hurry up and get the case on the docket so that he didn’t have to live with her anymore,” recalled Griffin.

A judge here has even set up a wellness room for the clerks. Although, in reality, Griffin said few have had the time to use it.

What Lawmakers Can Do

The statewide shortage is in part because lawmakers have expanded judicial services without providing funding for the people who deliver those services.

In recent years lawmakers have created eviction diversion programs, legislated better enforcement of restitution, and increased the number of judges. What they haven’t done is alloted funding for more clerks.

Karl Hade says that’s made it increasingly challenging for Virginia’s court to effectively do their jobs. He says it’s already at crisis level.

“We’re doing it the best we can because of the dedication of the staff that we have. But we can’t, we can’t keep up with this pace,” said Hade.

An analysis by his office shows Virginia’s district courts need 276 more clerks for the existing workload. But the Supreme Court’s office isn’t even asking lawmakers for that much. It’s asking for about $11 million to hire 120 new clerks over the next two years.

“We need to show the employees that we’re trying to get them help,” said Hade. "We know we're not going to get all 276, that just doesn't happen in government, you don't get everything that you need when you need it."

The Governor’s office is currently drafting his proposed budget. A spokeswoman says they’re aware of the concern, and "this funding request is being considered as part of the governor's budget process."

The entire judicial branch eats up less than 1-percent of Virginia’s budget, and asking for more clerks is an increment of that. But in recent years lawmakers have denied the request.

"They deserve more. And they love the work too otherwise they wouldn't be here."

Hade says clerks may fly under the radar because, unlike teachers or police officers, they aren’t often represented at the capitol.

“The clerks can’t really show up at the General Assembly en masse and lobby for better pay,” Hade said. “The judicial branch has got to be seen as impartial and apolitical.”

In addition to hiring more, Hade would also like to raise salaries.

Clerk Carrie Hamelink has to work a second job to help support her four kids. But as a supervisor she still makes more than the clerks under her. Starting pay is about $30,000.

Hamelink gets emotional thinking about how some of her staff have to make ends meet.

“They do a lot of work. And they’re not compensated for it,” Hamelink said. “They deserve more. And they love the work too otherwise they wouldn’t be here. But we do have a high turnover rate. Because of the pay, and the workload.”

In the survey mentioned earlier, clerks talked about stress, low morale, and a sense of hopelessness. At the court in Chesterfield some women have had to move back in with parents or forego buying medication. Clerk of Court Linda Moore has even had to sign the eviction papers herself for some of her staff.

Those circumstances make it tough to retain people.

“It’s prime picking for any clerk’s office for a law firm to come and grab employees,” said Moore.

When that happens Moore has to hire and train a replacement, which she says can take up to a year. Training documents for a JDR court outline a two-year process.

Despite those challenges Moore would still recommend the job to a young person today.

“There is nothing else like it out there,” Moore said. “There is no office job anywhere that is comparable to this branch of government.”

***Editor's note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the Clerk of the Supreme Court of Virginia briefed legislators on the issue. It has been corrected to Executive Secretary of the Supreme Court of Virginia.

This report, provided by Virginia Public Radio, was made possible with support from the Virginia Education Association.